April is the month when the International Monetary Fund (190-member countries) and the World Bank (189-member countries) undertake the first of the two biannual reviews of world economy, which are discussed at their meetings held in Washington. The next bi-annual meeting with the second review is in October. The regional development bank for Asia, the Asian Development Bank (68 member countries) held its annual meeting on May 1-3.

The Indian economy declined in 2019 for various reasons, which included lingering impact of demonetisation and the growing banking crisis with mounting non-performing assets and persistent, poor export performance. Added to these domestic factors, a confidence crisis in the minds of short-term asset holders resulted in the pulling out of hot moneys, which was compounded by the falling external value of the rupee.

The spread of Covid-19 was fast. Aside from loss of lives due to the deadly virus, the partial and ineffective lockdowns ensured fall in production, and cut in job numbers and the resultant lays-off and consequential decreases in personal incomes and reduced consumption and contraction of demand. Reduced savings and reluctance to invest when returns are uncertain, added more to economic woes. Decreasing domestic aggregate demand which was compounded by poor export performance since the early 2000s saw the beginning of the Covid- 19- induced depression.

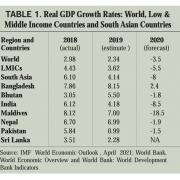

Data on estimates of world output in 2020 show that the world economy contracted by 3.5% (Table 1). Economic growth of Asia as a region shrank only by 0.25%, since China, the second largest economy of the world, also being the largest economy in Asia is reported to have not only survived but thrived. It expanded by 2.3%, which reduced Asia’s contraction to a smaller degree.

The ADB’s May 2021 Asian Development Outlook (ADO) reports that South Asia, as a sub-region, recorded the biggest contraction in 2020. India, which is the largest economy in South Asia, with its 8.5% contraction pulled down the sub-region’s growth rate of real GDP, although Bangladesh performed a lot better.

Emergence of new variants

Although it seemed that the global spread came under control in the third quarter of 2020, new variants of Covid-19 emerged in the last quarter in Europe - giving rise to another bout of concerns with a new spell of outbreaks. Asia’s incidence of Covid-19, which reached the peak with new cases of 106,000 per day in September 2020, fell to 32,000 by the end of February 2021. Discovery of vaccines toward the end of 2020 and their approval instilled hopes. India’s vaccination production started in earnest.

India, with false signs of dip in new domestic cases, shipped a huge consignment of vaccines to friendly countries in Latin America, Maldives and others. There was a lull in the spread, before a severe storm broke out, beginning in late March 2021. The latest report is that daily new cases are rising since mid April 2021. It is now more than 400,000 cases/day and thr cases are spreading fast in rural areas. The share of rural districts has risen to 49% in May compared to 37% in March. With greater demand for vaccination, India is now experiencing acute supply shortages in vaccines. A State Bank India (SBI) study released on May 6 says that 160.5 million doses of vaccine have been administered; 131 million with one dose and 31.5 million fully vaccinated taking both doses. The percentage of people who have taken double dose to total vaccination doses is now around 19.5% and the daily vaccine doses given is now at an average of 17 lakhs per day. At this rate, SBI predicts the country will only be able to vaccinate 15% of the population by October 2021. For herd immunity, it is estimated that vaccination should take place at around 55 lakhs daily in September and October. This confirms a similar research finding by an IMF study, though in the context of a global scale, that the complete global coverage by the middle of 2021 is unlikely.

Drying up of two external sources

In the past, when both domestic demand and supply forces were weak, there were some favourable external demand and supply forces which came to the rescue. The once dominant foreign aid on an annual basis, without any quid pro element, in terms of pure grants from government to government has now been phased out by advanced countries, except in dire circumstances such as earthquakes and cyclones. The other is Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) which is a private sector affair and subject to severe fluctuations. We refer here to FDI by foreign manufacturing and service providing companies who add to physical investment in capital goods and contribution to training and transfer of skills. FDI is subject to conditions of political stability and confidence in the governments of the host country. The flow of hot money, in search of favourable interest rate differential in the short run (less than a year) is in equity or short-term bonds. Now the trend, in the context of Covid-19 is that overseas private investors are pulling out their short-term equity and bond money for seeking “healthier” economies. That brings us to the discussion of two external resources, which were consistently available to all developing countries. They are inward remittances and tourism. We will deal with remittances this time, reserving the topic of tourism earnings for the next issue.

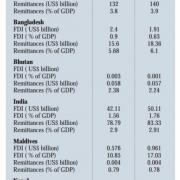

Table 2 provides data on remittances and FDI for the world as a whole and includes the world’s low and middle-income countries and South Asia as a whole. Inward remittances are far greater than FDI for all countries except Maldives, which is an upper middle-income country. It receives tourism infrastructure oriented FDI much more than remittances, as its migrant stock is the smallest among SAARC countries.

< TABLE 2 to be inserted here >

In pre-pandemic 2019, the top five remittance recipient countries were India ($83.1 billion), China ($68.4 billion), Mexico ($38.5 billion), the Philippines ($35.2 billion), and the Arab Republic of Egypt ($26.8 billion). With India’s migrant stock being the second largest in numbers, next only to Mexico’s, the blue-collar workers’ remittances are regular, although smaller in size. They are intended for supporting their families left behind in India, contributing to poverty reductions as well as supporting education of the young ones and medical expenses of the aged in the family. Occasional but more sizeable amounts are sent by highly qualified professionals of Indian origin and those residents working on temporary basis in advanced countries - including the US.

All remittances, being in foreign exchange are real resources. They are additions to India’s foreign exchange reserves. In the context of declining export earnings, remittances have emerged to be a major support to India’s balance of payments. Current account deficits, thanks to remittances, have remained smaller and manageable. Further, in the absence of remittances, the deficits would have been much larger and pressure on Indian rupee would have been much greater.

As the full data on remittances for 2020 is not available, preliminary estimates reveal remittances to LMICs would fall from the record high of $554 billion in 2019 to $508 billion in 2020 and to $470 billion in 2021. This has been noted to be the sharpest decline in recent years. The current oil crisis is now emerging as a supply propelled crisis. With a demand-oriented crisis following the falling incomes there has been a consequent drop in production and rise in unemployment and layoffs. Further with the cancellation of major events such as Dubai Expo 2020, many lost jobs in 2020. About 400,000 Keralites - working in West Asia - had to return home.

Only two countries in South Asia, Bangladesh and Pakistan experienced surges in inflows of remittances in July 2020. Their overseas migrants who had saved money for travel to Mecca decided to send it home because of steep reduction in the issue of visas by Saudi Arabia for preventing the spread of the pandemic. The World Bank’s migration portal registers this as the Haj effect, which enabled a rise in remittance inflows for both, Bangladesh in particular recording a 53% increase in 2020.

With the existing uncertainties, the government authorities should not tinker with remittance inflows. It is understood that banking and financial institutions which are now the preferred way of transferring funds by migrants are trying to impose charges for conversion into rupees. On April 1, the government shocked the nation with a poor decision. The interest rate on Public Provident Fund was lowered from 7.1% to 6.4%, and that on National Savings Certificates from 6.8% to 5.9% for the June quarter. The order was later withdrawn.

Dr. T K. Jayaraman is a Honorary Visiting Professor at Amrita School of Business, Bengaluru Campus. He is also a Research Professor at the University of Tunku Abdul Rahman, Faculty of Business, Accounting and Finance, Kampar Campus, Perak, Malaysia.

Add new comment