Each quarterly estimates of GDP is taking India’s $5 trillion economy target further away. At this rate the country will take about a decade to reach there – far after the original schedule of 2024-25.

GDP growth has fallen for the seventh consecutive quarter – down to 4.5% in the second quarter of the current year. This is a decline of 0.5 percentage points over the first quarter and a huge 2.5 percentage points compared to the second quarter of last year, when it grew by 7%. The GDP growth in the second quarter of the current fiscal was the slowest in more than six years. The previous low was recorded at 4.3% in the fourth quarter of 2012-13. The sharp fall in second quarter growth figures now makes it almost impossible to reach even the lowered growth projections for 2019-20.

The RBI has already reduced its growth forecast for 2019-20 to 5% from the 6.1% that was projected earlier. The Monetary Policy Committee noted that a delay in revival of domestic demand, further slowdown in global economic activity and geo-political tensions pose downside risks to growth.

The fall has been widely spread over the sectors; be it agriculture, manufacturing, construction, real estate or financial intermediaries. The worst hit was the manufacturing sector. The gross value added of the manufacturing sector in the second quarter of the current year has actually declined by 1% compared to a 6.9% rise in the corresponding quarter of the last year. This, however, has not come as a surprise since right from the beginning of the current fiscal, the monthly index of manufacturing output has been dithering. The index declined by 3.9% last September against an increase of 4.8% in the same month a year ago. The cumulative manufacturing output has grown by 1% during April-September 2019 compared to a 5.4% rise in the same period last year. On the other hand, the growth of core industries that reflects the prospect of future economic activities fell to 0.2% during April-October 2019 against a rise of 5.4% in the same period a year ago.

There are several reasons for the slowdown, from falling global GDP growth to trade tensions between China and the US to falling investment and export. However, back home the prime villain has been the falling consumption expenditure. This is reflected in sharp fall in the share of private final consumption expenditure in GDP. The share has gone down by one percentage point between the first quarter of 2018-19 and the first quarter of 2019-20. The decline has been very sharp in the last three quarters – down by a huge 2.6 percentage point from 58.9% in the third quarter of 2018-19 to 56.3% in the second quarter of the current year.

This is reflected in the falling consumer confidence index. According to the RBI’s latest Consumer Confidence Survey, the consumer confidence dropped to a five years low last November. The Current Situation Index (CCI) declined to 85.7 in November 2019 from 89.4 in September round of the survey. In March 2019, the consumer confidence was 104.6 and crossed the 100 mark for the first time after the December 2016 round. However, this jump was transitory. In the subsequent rounds the consumer confidence index was on a free fall.

The Finance Minister has taken a number of measures in recent months to boost credit in the market - focusing on offering incentives to banks to increase lending to prop up investment but these measures have failed to make much impact so far.

Former chief statistician of India, Pronab Sen, reportedly, argues that the FM’s recent packages have focused largely on the supply side while the real problem is falling demand. “The FM’s measures don’t address the problem of demand contraction. I don’t see a recovery out of those,” he says, adding that the economy will recover in two or three quarters only if the government quickly shifts its attention from mega highway projects to smaller core sector activities that have a quicker turnaround time.

The big question is how to reverse the downtrend? Apparently, raising consumption expenditure is the key to the revival of the economy right now. Higher demand will improve output generation; create more jobs and incomes which in turn, will increase domestic demand.

For that the economy needs more investment, especially, in the private sector. With so many expenditure obligations, the latest being the proposed revival package of BSNL and MTNL, the government will find it difficult to spend over the budgetary allocations without distorting its fiscal deficit target, which is already under pressure. Keeping that in mind, the FM has announced a massive cut in corporate taxes last September to leave more funds in the hands of industrialists for investment.

In a major move to stimulate the country’s ailing real estate sector, the government has decided to set up a `25,000-crore alternative investment fund (AIF) to revive a large number of stalled housing projects across major cities in the country. The AIF will be a special window to provide priority debt financing for completion of projects in the affordable and middle-income categories.

To attract more foreign capital, the government has diluted the stringent condition of local sourcing for single-brand retail, allowed 100% FDI in commercial coal mining and has increased the FDI limit in insurance intermediaries to 100%.

At the other end, the central bank has steadily cut the policy rate to make funds cheaper for industries. After the last October’s cut, the repo rate stood at 5.15% and reverse repo rate at 4.90%. In total, the RBI cut key rate by 135 bps starting from February 2019 in five successive steps. RBI, however, has kept policy rates unchanged in its last December monetary policy.

The move may have belied corporate expectations, but if one looks from a different angle, this may help revive the household consumption. The purpose of cutting interest rate was to provide cheaper funds for investment. But in reality, it has mostly helped the government, the biggest borrower. Industrial investment depends more on expected return on investment than on availability of cheaper funds. Industry would invest if it finds the expected return sufficiently attractive over whatever the cost of fund may be. And for this it requires demand, which has been falling unchecked.

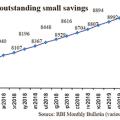

And who are the consumers? The answer is: The households. As has been observed by different consumer confidence surveys, Indian households are withholding consumption for fear of future uncertainty. They are instead, keeping the money in small savings schemes, which give better return, or in bank term deposits. Worse, contradicting the conventional economic theory, their saving propensity has been rising with every cut in interest rate. This is reflected in the sharp rise in small savings collections. Total outstanding small savings in the country have gone up about 14% in one year, from `7,920 billion in February 2018 to `8,992 billion in February, 2019 (the latest available figure).

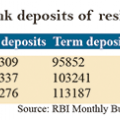

At the other end, total term deposits of commercial banks have gone up by about 10% from `1,03,241 billion on last Friday of September 2018 to `1,13,187 billion on the last Friday of September 2019.

The government would feel happy that so much money would be available for giving advances, but the basic predicament remains that much of it is remaining idle for lack of credit demand. According to a research report by ICRA, credit growth in India would by 8-8.5% in 2019-20 – a sharp fall from 13.3% in the previous year. Validating ICRA’s report, RBI data show that between the last Friday of September 2018 and that of September 2019, the non-food credit of scheduled commercial banks have grown by 8.6%.

The questions across the country are: How long will the slowdowns continue? How many more quarters will pass before India can bounce back to its desired 8-10% growth trajectory? There is no answer yet.

Add new comment