“I have no special talent. I am only passionately curious”- was how Albert Einstein defined the role of education in life. Education would create curiosity and open up new horizons of knowledge. But for that, proper infrastructure needs to be provided. The government has the foremost role to play in this.

In India, the major issues in education today relate to this role of the government. Education was a state subject but there were some provisions in the Indian Constitution which contradicted the absolute delegation of authority to the states. A lot of controversy regarding the constitutional provisions of education brewed for some time. In 1976, this controversy was put to rest by a Constitutional Amendment. Education was put on the Concurrent list. The implications of making education a concurrent subject is that both the Centre and the states can legislate on any aspect of education from the primary to the university level. By having education in the Concurrent list, the Centre can implement directly any policy decision in the states.

This amendment has made Central and state governments equal partners in framing educational policies. The executive power is given to the Union to give direction to the states. The states have powers limited to the extent that these do not impede or prejudice the exercise of the executive powers of the Union.

Backed by constitutional provisions, the central government has shown unprecedented activity and interest in the field of education over the years. Fund-struck states have acceded to the Centre’s increased monitoring and involvement.

Education is now largely paid for and administered by government bodies or non-profit organisations in the country. This situation has developed gradually over the years and is now taken so much for granted that the dependence on the government has resulted in an indiscriminate extension of governmental responsibilities.

A stable and democratic society needs to nurture and develop some common set of values. To achieve them a minimum degree of literacy and knowledge on the part of most citizens are prerequisites. Education contributes to both and thus, the role of the government in a country like India where most students suffer from fund crunch, is significant. Apart from the designing of the education system, what is more important is the money provided by the government to further education.

The Union government’s involvement in education has increased, but the question is: Is the government spending enough to meet the needs of the changing demand of the time? The answer is: No. In fact, the share of education in Centre’s total spending has declined in recent years.

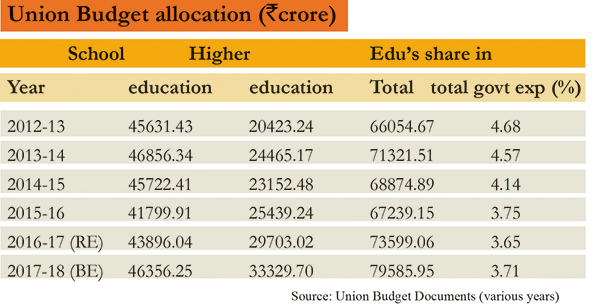

In the last five years, between 2012-13 and 2017-18 (BE), spending on education as a share of the Central government’s total budgeted expenditure has declined by almost one percentage point from 4.68% to 3.71%. And this fall has been steady over the years except in 2017-18 when it has gone up by a paltry 0.06 percentage point over the revised estimates of 2015-16. There is, however, a catch that this was only a budget estimate subject to a change during the year. And although the budget allocation of the Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD) has increased by about 8% in 2017-18 over the revised estimates of 2016-17, this was largely illusory because inflation of about 5-6% would neutralize much of it.

Since 2016-17, the government has rejigged the sharing pattern of central schemes in key sectors including secondary and higher secondary education with lower 4 outlays in the Budget and more direct transfers in keeping with the recommendation of the 14th Finance Commission. This may have contributed marginally to a decline in the total education outlay as allocation for two schemes concerning secondary and higher education – the Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan and the Rashtriya Uchchtar Shiksha Abhiyan – were made beyond the budget allocation on education. These two schemes together accounted for about 7% of the total education outlay in 2015-16.

But more than the share in budget allocation, what will probably give a better idea of the government’s initiative in furthering education is the share of expenditure on education in gross domestic product (GDP). Looking at the education spend as a share of the GDP, which is what most of the international trackers do, the trend is disappointing to say the least. Like in the share of budgetary allocation, here too, the share has been declining unchecked. From 3.3% in 2012-13 the share has gone down to 2.9% in 2017-18.

When compared globally, this would look really poor. While most of the developed countries spend 5% or more of their GDP on education some of the less developed African nations have scored over this figure in recent times. According to World Bank data, Ghana spent about 8.2% of its GDP of education in 2013. Congo spent 6.2% during the same period. India’s fellow BRICS countries, Brazil and South Africa spent 5.8% and 6.2%, respectively, during the same period. The US, Germany, and France spent in excess of 5% of their GDP on education in 2013.

One may remember that almost half a century ago the Kothari Commission first recommended to increase the public spending on education to 6% of India’s GDP. But despite repeated mentions in successive National Education Policies and in the poll promises of various governments — India is far from meeting the goal.

Indian states at the other end are, however, allocating a considerably higher share of their total budgetary outlay on education – they are spending on infrastructure, maintaining it and paying mostly for the teachers and other education related employees for both schools and higher level education. About a sixth of the total budgetary expenditure of the Indian states now goes to pay for education. Some states such as Assam (21%), Chhattisgarh (19.7%), Himachal Pradesh (19.1%), Maharashtra (18.2%), and Madhya Pradesh (17%) allocated a considerably higher share of their total expenditure on education in 2016-17 budget compared to 15.6% of the average allocation of all states.

These are not mere statistics. The stake is high as the public spending on education is a must for making quality education accessible to all. While the government has been congratulating itself time and again for bringing almost all the children aged 6-13 years to elementary school, little attention has been paid to the fact that after this stage, it is downhill all the way. Gross enrollment ratios (number of students in school at a particular stage as a percentage of all children in the concerned age group) rapidly deteriorate after elementary school, going down to just 54% by senior secondary level. In other words, roughly half the children are out of school by the time they are senior school age. This works out to about 35 million kids out of school. In higher education, the situation is much worse, with an enrollment ratio of just 24% for the 18-23 age group. This includes distance education students.

There are worse indications coming from UNESCO, which in its report last September warned that India will be half a century late in achieving its universal education goals. The Global Education Monitoring report of the UNESCO has said that the 2030 deadline for achieving sustainable development goals will be possible only if the country introduces fundamental changes in the education sector.

Add new comment